Mosquito Control And The Zika Virus

The possibility a mosquito bite during pregnancy could be linked to serious birth defects in newborns has alarmed the public and astounded scientists. For women of childbearing age living in or visiting affected countries, the prospect of giving birth to a baby with such acute defects is terrifying.

The organization of virus circulation with an elevated detection of Guillain-Barré syndrome adds to the issue. GBS is an autoimmune disorder with various causes, including infections with some viruses and bacteria such as Campylobacter jejuni. In a few of these nations, the fact that Zika is the only circulating flavivirus adds weight to the organization that is presumed.

In countries with advanced health systems, around 5% of patients with the syndrome expire, despite immunotherapy. In an intensive care unit, sometimes for months up to a year, adding to the burden on health services, many require treatment, including ventilatory support.

The societal and human impacts for the over 30 nations with recently detected Zika outbreaks will be staggering if these presumed associations are affirmed.

Where and When Zika First Hit

In the large outbreaks that changed some Pacific island nations, first in 2007 and again in 2013-2014, and then spread to the Americas, Zika virus has often co-circulated with dengue and chikungunya viruses. When the virus is replicating, also infection can be detected by the currently accessible PCR test just during the period of sickness, a weakness further compounded by the fact that 80% of infections cause no symptoms. Although Zika vaccines, WHO estimates that it will be at least 18 months before vaccines are being worked on by at least 15 group,s could be tested in large-scale trials.

For all these reasons, WHO urges stepped-up private and population-wide measures for mosquito control as the best immediate line of defense.

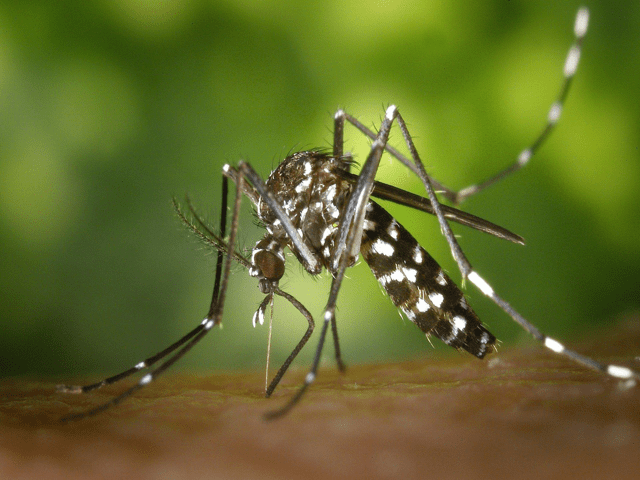

Aedes aegypti: a “opportunistic, tenacious and” threat

Aedes aegypti is the primary mosquito species that transmits yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika to humans. More than half of the world’s population lives in areas where this mosquito species is present.

Experts describe Aedes aegypti as opportunistic, as it shows a remarkable ability to adjust to changing environments, particularly those created by changes in the manner mankind inhabits the planet. Over the years, it's used these opportunities, which include exceptional increases in international travel and commerce and fast unplanned urbanization, with striking efficacy. Most ominously, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which long reproduced in water gathered in tree holes and the axils of plant leaves in forests, have adapted to reproduce in urban areas, thriving in impoverished crowded places with no piped water and badly collected garbage and litter.

Combatting Zika where it Thrives

The mosquitoes can breed wherever water or rain gathers, is stored, with predilection for outside breeding sites. Larvae have been found in a host of man-made containers, like bottle caps and cast-off plastic cups, plates under potted plants, birdbaths, vases in graveyards, and water bowls for pets. The mosquitoes may also reproduce in the microbial stew found in toilet tanks, septic tanks, and shower stalls. Building sites, used tyres, and clogged rain gutters offer additional opportunities to breed in large numbers.

Laid eggs can survive for very long intervals in a dry state, often for more than a year. They hatch instantaneously once submerged in water. Mosquitoes can stay in the larval phase for months so long as the water supply is sufficient, if temperatures are cool. The eggs are sticky, essentially pasting themselves to the insides of containers. International trade in used tyres is the best documented vehicle for introducing the mosquito to distant locations.

Females: aggressive biting and “sneak strikes”

Aedes aegypti is a competitive biting mosquito that is day. Only the females bite. Biting is most intense in the hours around twilight and dawn. Indoors, the mosquitoes can bite at night in well-lit houses. They may be adept at hiding in closets and under beds.

Females often use “sneak strikes approaching casualties from behind,” and biting on ankles and elbows, which probably shields them from being discovered and getting slapped.

Aedes aegypti females are so-called “nip feeders”. Instead of drawing blood that is sufficient for a meal within a bite, they take multiple little sips during multiple bites, so raising the number of individuals a single mosquito can infect.

Unlike most other mosquito species, a female Aedes aegypti can generate up to 5 batches of eggs during her lifetime. As yet another survival tactic, one female lays her batches of eggs at several different sites.

All of these attributes make Aedes aegypti populations extremely difficult to restrain. They also make the diseases they spread a much bigger threat.

Mosquito Control Proves Successful

After the discovery and successful use of residual insecticides in the 1940s, large-scale and systematic control programmes succeeded in bringing most of the significant mosquito-borne diseases in many parts of the world under control. Aedes aegypti was virtually removed from the Americas. By the late 1960s, most mosquito-borne diseases were no longer considered to be significant public health issues outside Africa.

The control program expires as so frequently happens in public health, when a health danger subsides. Resources dwindled, the control program fell, the infrastructures dismantled, and fewer specialists were trained and deployed. The diseases they transmitted – and the mosquitoes – roared back with a vengeance. Almost 2 decades of diminishing interest and dwindling expertise seriously weakened national capacities to execute a program for mosquito control. Previously successful control programs were replaced by the reactive space spraying of insecticides during emergencies, a measure with high exposure and political appeal but low impact unless integrated with other control strategies like those offered at Pest Assassins.

The weakness – sometimes disappearance – of control ability coincided with tendencies, like accelerating population growth, accelerated unplanned urbanization, and changes in patterns of land use, which made environments even more hospitable for booming Aedes aegypti populations.

Additionally, the armory of effective insecticides shrank as mosquitoes developed resistance.

The recent history of dengue best illustrates the effects of this remarkable comeback. Compared with the situation 50 years ago, the global prevalence of dengue has climbed 30-fold. More countries are reporting their first outbreaks. More outbreaks are volatile in ways that severely disrupt the drain markets and societies.